Background And History

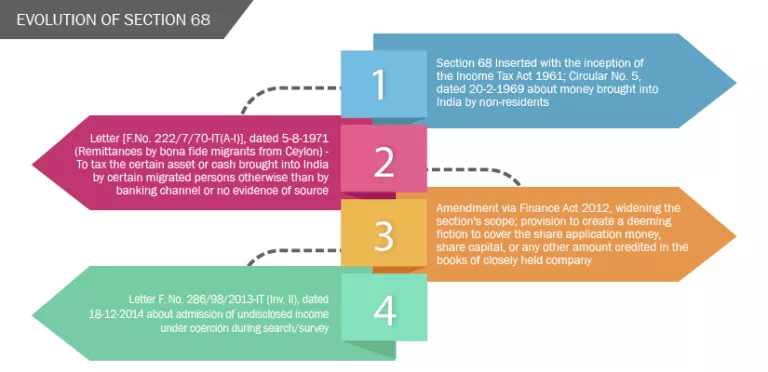

Section 68 was introduced in the Income tax Act, 1961 with effect from 1st April 1962. The said section was unique at the time of its introduction as there was no provision corresponding to Section 68 in the erstwhile Income Tax Act, 1922.

It was introduced to incorporate the rule of evidence, i.e., to cover cash credits in the books of the taxpayer, maintained for a particular financial year for which the taxpayer failed to offer an explanation, or if the explanation given was not satisfactory to the tax officer about the nature and source of such cash credit. Consequentially, such cash credit was to be considered as part of the income of the taxpayer for that financial year.

Over the years, there were amendments in Section 68 of the Act, a brief overview for the same is as follows:

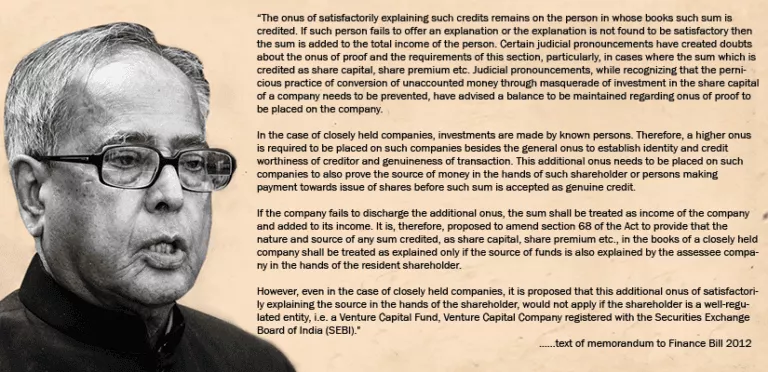

Following the Finance Bill 2012, the Tax Department increased the scope of Section 68 with an aim to clarify the onus of satisfactorily explanation.

Practices Before The Amendment

For e.g., the company XYZ Private Limited (the ‘taxpayer’) used to adopt the following modus operandi to convert black money into white money.

- 100 slum-dwellers were considered, and INR 1 Lac in cash wash deposited in each of their bank accounts and cheques of INR 1 Lac were taken from them in the name of tax payer. They were made to sign the share application money to apply for 5,000 shares of face value INR 10 each, at INR 20. They were also made to sign the blank share transfer deed. The return of each slum dweller was filled, showing an income of INR 1 Lac and tax thereon as nil. For this process, each slum dweller was paid INR 2,000 in cash (i.e. unaccounted money)

- From the above process, we see that the company has deposited INR 1,00,000/- in cash, in the bank account of 100 slum dwellers, i.e. the total unaccounted money of INR 1 crore, and has received cheques from the slum-dwellers. The fair market value of the shares of XYZ Pvt Ltd is now INR 20 per share. The company XYZ Pvt Ltd can either show INR 1 core as share application money or allot 5,000 shares to each slum dweller.

- During the assessment, when the tax officer asks for the documents, the company produces the name, address, PAN Number and ITR of the slum dwellers. The company does not produce their passbooks and does not produce them personally before the tax officer during the assessment, either.

- The tax officer invokes Section 68 and adds INR 1 crore in the income of the company as unexplained cash credit, since the person from whom the amount of share capital received was not able to prove the source of the money in their hand. The tax payer files an appeal to the Supreme Court of India where the court held that, if the share application money is received by the tax payer from alleged and bogus shareholders, whose names are given to the tax officer, the tax department is free to proceed to reopen their individual assessments in accordance with law but this time amount of share money cannot be regarded as undisclosed income u/s 68.

- The Supreme Court held that there is no onus on the company to provide the source of money in the hands of the shareholder or the person making the payment of share application money. Therefore, if the company identifies the person from whom money has been received, Section 68 can’t be invoked in the hands of the company.

- In the company’s hands, no income can be added and even if the slum dwellers had no explanation on the source of INR 1 Lakh in their hands, no income tax can be computed since the income earned is only INR 1 Lakh.

- Thus, INR 1 Crore of black money was effectively converted into white money with no tax implications.

After The Amendment

Finance Act 2012 nullified the above tax planning by inserting a provision in Section 68, which overruled the Supreme Court judgement in the case of Lovely Exports Pvt Ltd.

Provision to The Section

Under this provision of Section 68, in case of a closely held company, i.e., a private company or a penny stock company being a tax payer issuing a share capital or receiving share application money/share premium or any such amount, any explanation offered by such tax payer shall be considered to be not satisfactory, unless the person (i.e., the investor or payer), in whose name such amount is recorded in the books of such tax payer:

- is a resident

- offers an explanation about the nature and source of sum so received; and

- such explanation in the opinion of tax officer is found to be satisfactory.

When the investor is not able to explain the nature and source of the sum invested or the explanation is not satisfactory to the tax officer, the sum received towards share capital/premium shall be added to the income of the tax payer.

However, the provision inserted in Section 68 would not be applicable to a venture capital fund or a venture capital company, since they are regulated by SEBI.

The above provision has been introduced with an obvious objective to curve out the pernicious practice of conversion of unaccounted money through masquerade of investment in the share capital of a company. This was a positive move from the government to stop the circulation of black money in the Indian economy.

Our point of concern is on the current practices adopted by the Indian tax officers, who purposely level allegations on Indian subsidiaries or companies (‘tax payers’) receiving the amount of share application money from their non-resident (‘NR’) parent company or NR investor as ‘unexplained cash credit’.

India has been at the forefront in the list of countries attracting foreign investment and it is true that India needs foreign capital. However, while receiving FDI at a large scale, it is also important that the colour of money being flown as FDI is not wrong.

On similar lines, tax laws allow the tax department to seek explanation on money received as share capital and understand the identity, genuineness and creditworthiness of the overseas investor. Consequently, taxpayers are being asked to provide financial data of the non-resident investor(s) to assess the genuineness and credit-worthiness of the investor.

There are various regulations such as Prevention of Money Laundering Act and certain processes under Foreign Exchange Management Act which require the transacting banks, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the concerned Indian investee company to provide documentation at the time any foreign investment is received in India.

The process requires filing of Form FC-GPR, which will invariably establish the identity of remitter as well as a confirmation from remitter bank regarding its relationship with remitter. In addition, if the remitter is the original shareholder of Indian company, it would have already submitted its legalized (including attestation by Indian embassy in the respective country) and notarized corporate documents with the Registrar of Companies (RoC).

A foreign investor, being outside the jurisdiction of the Indian Income Tax Act, is not obligated to provide financial information in India. Other information such as name of the investing entity, their basic corporate documents, etc. are included as part of RBI’s compliance documentation.

Given the above, any request from the Income Tax Department for submission of financial data of the investor company is likely to put the Indian taxpayer in an awkward situation vis-a-vis tax department and its shareholder.

Considering that it is important to strike the right balance, we need to go back to the original purpose of the introduction of Section 68 of the Income Tax Act. One of the purposes of Section 68 is to probe any sort of money laundering and conversion of black money.

In an international scenario, such kind of malpractice is often carried out through round-tripping or hawala transactions. Since there are existing laws (such as treatment of difference between fair price and transaction price, where the resident buys the shares at less than market price, as income for the buyer) and regulations to check such malpractices to begin with, it would prove important to seek relevant documentation used in compliance of these laws such as the FC-GPR documents or the entity’s incorporation documents, in case the original investor is investing.

From the taxpayers’ point of view, one of the things that can be done is to seek notarized and apostilled corporate charter documents of the investors at the time the investment is done. Even though there may not be a statutory requirement considering the time limitation at the time of tax audits, having such documentation in place will prove beneficial in establishing the identity and genuineness (to an extent) of the investor. In addition, the documentation available on public registry in the respective countries can also be produced.

Hence, it’d be better to define certain parameters where the Government believes dubious transactions may have happened and the concerned field officers should dive deep only in those transactions.

For example, the cases where investment is made by an overseas private equity fund or a listed public entity, those transactions can be considered for exemption from detailed scrutiny. Overall objective of investment and subsequent use of capital may be analysed to see if there is any possible mala fide intention behind the investment.

Submission of RBI and Registrar of Companies (ROC) compliance documents can be made mandatory, and if the perusal of those documents shows glaring gaps or non-compliance, further investigations can be conducted. Even in such situations, the matters may be referred to FT&TR for investigation so that appropriate information can be obtained through right channels. But applying the same process for every transaction will inevitably become a pain-point for genuine investors as well as the tax department.

Hence, the question will always be to decide the priority. While it is the prerogative of each successive government, we believe promoting entrepreneurship and capital investment should always remain at the forefront to ensure a progressive economy.

–

Written By

Nupur Sharma & Tanuj Rawat, in collaboration with the Coinmen Research Team